I'm a little late to the party, but in case anyone missed it, I wanted to point out the winners of the 2011 Fids & Kamily Music Awards, which were announced back on November 19th. Many of my own favorite albums of the past year made the list. (I'm flattered to be among the voters, so that's not entirely a coincidence—though it's nice to see I'm not alone in my appreciation of Recess Monkey, Frances England, Lunch Money, and the rest!)

Anyway, if you're looking for some good kids' music for year's end—whether you're after the latest from a big name like Dan Zanes or a gem from an artist you didn't know before—this list is an excellent place to start.

November 30, 2011

November 29, 2011

New Movies: Hugo

As huge fans of Brian Selznick's book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, our family was very interested in the film version. Its director, Martin Scorsese, seemed a great fit for a story so steeped in the early days of moviemaking, so my usual low expectations for adaptations of beloved books were not quite so tempered. We rushed out to see it the day after Thanksgiving. (The boys, of course, were thrilled beyond belief, as they continue to be every time we actually go to a movie theater. It's one of those lovely things to watch that I know won't last forever, or perhaps even much longer.)

The film version of Hugo Cabret, as its shortened title—just Hugo—might imply, has had its story pared down and streamlined. Lovers of the book should be prepared for less depth, complexity, and just plain time given to its main storyline of a orphaned boy who lives in the walls of a Paris train station between the world wars, continuing his vanished uncle's job of keeping the station's many clocks running, and meanwhile trying to repair a complicated mechanical toy that represents, to him, his deceased father.

The movie zips through most of this—Jude Law, as Hugo's father, and Ray Winstone, as the uncle, have essentially just a scene apiece, though both manage to make remarkably strong impressions—to get to the part that, I imagine, is what drew Scorsese to direct the film: Hugo's interactions with the proprietor of a toy shop in the train station. This man turns out to be Georges Méliès, one of the first great directors of movies that told stories (as opposed to merely capturing true-life events on film).

And while it's fair to say that Hugo, perhaps inevitably, falls a bit short of its source material in terms of its main character's own story, when it comes to the Méliès stuff, it is able to exceed it. What were just images in Selznick's book—a still from Harold Lloyd's classic Safety Last!, as well as many from Méliès' own charmingly trippy films—come to life in the film as the full-blown cinema they are. And we couldn't be in better hands for this kind of thing. Scorsese has always been fond of magically capturing real historical events and references in his films—his re-creation of a famous Jacob Riis photograph in Gangs of New York comes to mind—and in Hugo, with the history of film itself to draw on, his excitement is contagious; when Scorsese portrays the excitement and the energy of Méliès's original shoots, we share in Scorsese's (and Méliès's) delight.

Of course, such excitement requires knowledge of the history itself, which means this aspect of the film—probably its best—is more or less lost on the kids. (Though I think Dash, our seven-year-old, got some of the wonder—Méliès' films are pretty magical, after all, outside of any historical context, or they wouldn't have been as popular as they were in their own time.) Happily, even the cut-down version of Selznick's story is engaging enough to keep most youngsters fully engaged; I’d say any child who’s able to fully process the book should have a great time. (In other words, as we should have realized it would be, the two-hour length was a bit much for our three-year-old.)

A great deal of the credit must be given to the actors, who fill out a screenplay that occasionally feels thin—particularly the two leads. Ben Kingsley is ideal as Méliès, able to convey the emotion of this wounded old man with a glance, and Asa Butterfield is a revelation (at least to those, like me, who didn't see him in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , I guess), capturing Hugo's desperation movingly. We found the rest of the cast equally admirable, mostly in roles that the film has built up significantly from the book, presumably in an attempt to lighten things up a bit. (The lone exception, surprisingly, was the ubiquitous Chloë Moretz in the key role of Méliès's niece, Isabelle, whose performance we found forced and even irritating at times.)

, I guess), capturing Hugo's desperation movingly. We found the rest of the cast equally admirable, mostly in roles that the film has built up significantly from the book, presumably in an attempt to lighten things up a bit. (The lone exception, surprisingly, was the ubiquitous Chloë Moretz in the key role of Méliès's niece, Isabelle, whose performance we found forced and even irritating at times.)

So no, Hugo doesn't deliver all the same joys the book did, falling well short of it in some ways. But it also manages to exceed its source in others, and that makes it a very enjoyable family movie. (I think many adults without young children will even find it so; I’m also very curious to know what those without prior exposure to Selznick's book think of the film.)

One last thing: 3D. Like so many movies these days, Hugo was shot in it. While I can see Scorsese figuring that Georges Méliès himself would have found modern 3D film technology pretty damn cool, I have to say that in the end, I didn't really see the point. The effect is certainly remarkable, a vast improvement on earlier, more primitive attempts at 3D moviemaking. But after the first five or ten minutes of "OK, that's pretty amazing," I found that I alternated between forgetting about it and, worse, finding it a distraction from the story. Maybe it’s yet another sign I’m getting old, but I think I'd opt for the 2D version—in fact, I’m seriously considering going back for a second screening in less-distracting 2D.

[Image © 2011 Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.]

The film version of Hugo Cabret, as its shortened title—just Hugo—might imply, has had its story pared down and streamlined. Lovers of the book should be prepared for less depth, complexity, and just plain time given to its main storyline of a orphaned boy who lives in the walls of a Paris train station between the world wars, continuing his vanished uncle's job of keeping the station's many clocks running, and meanwhile trying to repair a complicated mechanical toy that represents, to him, his deceased father.

The movie zips through most of this—Jude Law, as Hugo's father, and Ray Winstone, as the uncle, have essentially just a scene apiece, though both manage to make remarkably strong impressions—to get to the part that, I imagine, is what drew Scorsese to direct the film: Hugo's interactions with the proprietor of a toy shop in the train station. This man turns out to be Georges Méliès, one of the first great directors of movies that told stories (as opposed to merely capturing true-life events on film).

And while it's fair to say that Hugo, perhaps inevitably, falls a bit short of its source material in terms of its main character's own story, when it comes to the Méliès stuff, it is able to exceed it. What were just images in Selznick's book—a still from Harold Lloyd's classic Safety Last!, as well as many from Méliès' own charmingly trippy films—come to life in the film as the full-blown cinema they are. And we couldn't be in better hands for this kind of thing. Scorsese has always been fond of magically capturing real historical events and references in his films—his re-creation of a famous Jacob Riis photograph in Gangs of New York comes to mind—and in Hugo, with the history of film itself to draw on, his excitement is contagious; when Scorsese portrays the excitement and the energy of Méliès's original shoots, we share in Scorsese's (and Méliès's) delight.

Of course, such excitement requires knowledge of the history itself, which means this aspect of the film—probably its best—is more or less lost on the kids. (Though I think Dash, our seven-year-old, got some of the wonder—Méliès' films are pretty magical, after all, outside of any historical context, or they wouldn't have been as popular as they were in their own time.) Happily, even the cut-down version of Selznick's story is engaging enough to keep most youngsters fully engaged; I’d say any child who’s able to fully process the book should have a great time. (In other words, as we should have realized it would be, the two-hour length was a bit much for our three-year-old.)

A great deal of the credit must be given to the actors, who fill out a screenplay that occasionally feels thin—particularly the two leads. Ben Kingsley is ideal as Méliès, able to convey the emotion of this wounded old man with a glance, and Asa Butterfield is a revelation (at least to those, like me, who didn't see him in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

So no, Hugo doesn't deliver all the same joys the book did, falling well short of it in some ways. But it also manages to exceed its source in others, and that makes it a very enjoyable family movie. (I think many adults without young children will even find it so; I’m also very curious to know what those without prior exposure to Selznick's book think of the film.)

One last thing: 3D. Like so many movies these days, Hugo was shot in it. While I can see Scorsese figuring that Georges Méliès himself would have found modern 3D film technology pretty damn cool, I have to say that in the end, I didn't really see the point. The effect is certainly remarkable, a vast improvement on earlier, more primitive attempts at 3D moviemaking. But after the first five or ten minutes of "OK, that's pretty amazing," I found that I alternated between forgetting about it and, worse, finding it a distraction from the story. Maybe it’s yet another sign I’m getting old, but I think I'd opt for the 2D version—in fact, I’m seriously considering going back for a second screening in less-distracting 2D.

[Image © 2011 Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.]

November 18, 2011

New Books: A Dog Is a Dog

Picture books for the youngest readers can be many things—beautiful, moving, offbeat. But sometimes children (and their parents, too) are just looking for something, well, silly. Satisfying this common craving is Stephen Shaskan's new A Dog Is a Dog, a series of rhyming couplets illustrated in a pleasantly upbeat faux-retro style.

The book begins as if it's going to be merely about the various canine attributes. Until, that is, we get to the end of the first set of couplets—"A dog is a dog, unless it's...a cat!"—at which point the dog who'd been romping around the previous pages unzips himself to reveal that he's really a cat in a dog suit. (If you keep the premise from them, young kids will find this moment both truly shocking and hilariously funny; they may even need to pause before proceeding.)

From there, of course, we get more sets of couplets followed by more costume unzippings, which my little ones met with mounting hysteria. I won't give away the full menagerie here, but suffice it to say that a squid is involved at one point, before Shaskan neatly wraps things up by bringing back where we started. There's nothing terribly deep going on in A Dog Is a Dog—it's just very successful at being very silly indeed, in a novel way. And when that's what you and your kids are after, there's nothing more you could need from a picture book.

[Photo: Whitney Webster]

The book begins as if it's going to be merely about the various canine attributes. Until, that is, we get to the end of the first set of couplets—"A dog is a dog, unless it's...a cat!"—at which point the dog who'd been romping around the previous pages unzips himself to reveal that he's really a cat in a dog suit. (If you keep the premise from them, young kids will find this moment both truly shocking and hilariously funny; they may even need to pause before proceeding.)

From there, of course, we get more sets of couplets followed by more costume unzippings, which my little ones met with mounting hysteria. I won't give away the full menagerie here, but suffice it to say that a squid is involved at one point, before Shaskan neatly wraps things up by bringing back where we started. There's nothing terribly deep going on in A Dog Is a Dog—it's just very successful at being very silly indeed, in a novel way. And when that's what you and your kids are after, there's nothing more you could need from a picture book.

[Photo: Whitney Webster]

Labels:

children's books,

kids' books,

new books,

picture books,

Stephen Shaskan

November 16, 2011

New Books: The Cheshire Cheese Cat

In their new chapter book, The Cheshire Cheese Cat, Carmen Agra Deedy and Randall Wright put a couple of twists on the old "what if a cat and a mouse became friends?" trope (a favorite of mine ever since I first came across The Cricket in Times Square).

The first is that their cat protagonist, Skilley enters into a relationship with Pip, the mouse, initially as a business proposition: To get off the streets of Victorian London, he has become a mouser in a particularly infested pub. There's one problem, though: He doesn't eat mice—he prefers cheese. So he and the mice, represented by Pip, form a pact: He will catch them when in view of humans, then let them go when not. In return, the mice will give him ample portions of the pub's own delectable and proprietary cheese (which is stored in a place the mice can get to but cats cannot).

All is going swimmingly until another alley cat who does have the usual taste for mouse flesh enters the mix, and Skilley must find a way to protect his new friends. Complicating matters further is the presence of a grumpy, marooned raven in the pub's attic, whose absence from his Tower of London home, through a series of misunderstandings, risks becoming a reason for a full-scale war between England and France.

The second twist is that the pub in question happens to be the haunt of several of London's best writers, including Wilkie Collins, William Thackeray, and Charles Dickens, to the last of which this entire book is an homage. Dickens is having a bit of writer's block over the opening of his new novel about the French Revolution, and the goings-on at the pub prove to be a welcome distraction for him. In the end, the famous writer, the cat, and the mouse are able to do one another good turns, one of which has a monumental impact on literary history.

The Cheshire Cheese Cat, which also features illustrations by the formidable Barry Moser, is perfect in tone and spirit for young chapter-book readers, with enough adventure and plot twists to keep interest levels high without ever veering into anything truly upsetting or scary. It also may serve as an introduction to the work of Dickens himself, whose books are among the most accesible of adult classics to literary-minded kids. (If you're heading in that direction, by the way, I'd recommend starting with audiobooks, in which Dickens's intoxicating use of language comes across well—or, for the approaching season, A Christmas Carol. Or both!)

[Cover image courtesy of Peachtree Publishers]

The first is that their cat protagonist, Skilley enters into a relationship with Pip, the mouse, initially as a business proposition: To get off the streets of Victorian London, he has become a mouser in a particularly infested pub. There's one problem, though: He doesn't eat mice—he prefers cheese. So he and the mice, represented by Pip, form a pact: He will catch them when in view of humans, then let them go when not. In return, the mice will give him ample portions of the pub's own delectable and proprietary cheese (which is stored in a place the mice can get to but cats cannot).

All is going swimmingly until another alley cat who does have the usual taste for mouse flesh enters the mix, and Skilley must find a way to protect his new friends. Complicating matters further is the presence of a grumpy, marooned raven in the pub's attic, whose absence from his Tower of London home, through a series of misunderstandings, risks becoming a reason for a full-scale war between England and France.

The second twist is that the pub in question happens to be the haunt of several of London's best writers, including Wilkie Collins, William Thackeray, and Charles Dickens, to the last of which this entire book is an homage. Dickens is having a bit of writer's block over the opening of his new novel about the French Revolution, and the goings-on at the pub prove to be a welcome distraction for him. In the end, the famous writer, the cat, and the mouse are able to do one another good turns, one of which has a monumental impact on literary history.

The Cheshire Cheese Cat, which also features illustrations by the formidable Barry Moser, is perfect in tone and spirit for young chapter-book readers, with enough adventure and plot twists to keep interest levels high without ever veering into anything truly upsetting or scary. It also may serve as an introduction to the work of Dickens himself, whose books are among the most accesible of adult classics to literary-minded kids. (If you're heading in that direction, by the way, I'd recommend starting with audiobooks, in which Dickens's intoxicating use of language comes across well—or, for the approaching season, A Christmas Carol. Or both!)

[Cover image courtesy of Peachtree Publishers]

November 11, 2011

New Books: Wonder Struck

Brian Selznick's 2007 children's book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, followed the path of every author's fantasy: It got magnificent reviews full of words like groundbreaking; it won a Caldecott; it became that book every parent tells every other parent about; and—just to make sure Selznick would be pinching himself—now it's a major motion picture directed by Martin Scorsese. Not bad for his first time out there! Selznick deserved every bit of it, too; Hugo Cabret is marvelous. (If you and your kids haven't read it, I highly recommend it, as does a fellow critic somewhat closer to the intended audience.)

Still, being an inveterate worrier, I wondered how Selznick would follow up on his blaze of glory. The key innovation of Hugo Cabret—in what's otherwise a traditional chapter book, the author inserts ten-to-twenty-page sections in which the narrative is moved along purely through illustrations—seemed almost custom-made, in its cinematic nature, for that book's cinema-themed story. When I saw that Selznick's new book, Wonderstruck, would indeed use the same technique, I wondered if it would work as splendidly the second time around. Might it even start to feel gimmicky, more a narrative crutch than the revelation it had been originally?

About 40 pages into Wonderstruck, I stopped worrying. (And by the way, those 40 went fast—despite their daunting, tome-like size and heft, a side effect of those extended illo-only sections, Selznick's page-turners are surprisingly quick reads.) The author uses his two modes of narration to alternate between two deaf children in different time periods (the 1920s and 1970s) whose lives are mysteriously connected by a wolf diorama at New York's American Museum of Natural History, again expertly weaving real places and events (the 1977 NYC blackout, for example) into his story. And the almost cinematic nature of the illustrated sections retains loses none of its power here: The illustration in which the two stories come together, and we see the 1970s boy's face in an illustration for the first time, packs an incredible emotional punch that literally brought tears to my eyes.

Now, I will admit that by setting his story at this particular museum, and also using the amazing New York City panorama at the Queens Museum of Art as a key location for a vital moment of his story, Selznick had this Upper West Side–raised boy at hello. (There are also several knowing and most pleasing nods to the mother of all museum-based children's books, E. L. Konigsburg's From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.) Nonetheless, I'm confident that even those less steeped in NYC nostalgia than I am will enjoy Wonderstruck as much as I did. Which is quite a lot.

And in future, I will refrain from doubting Selznick's storytelling technique—and just enjoy it.

[Cover image courtesy of Scholastic]

Still, being an inveterate worrier, I wondered how Selznick would follow up on his blaze of glory. The key innovation of Hugo Cabret—in what's otherwise a traditional chapter book, the author inserts ten-to-twenty-page sections in which the narrative is moved along purely through illustrations—seemed almost custom-made, in its cinematic nature, for that book's cinema-themed story. When I saw that Selznick's new book, Wonderstruck, would indeed use the same technique, I wondered if it would work as splendidly the second time around. Might it even start to feel gimmicky, more a narrative crutch than the revelation it had been originally?

About 40 pages into Wonderstruck, I stopped worrying. (And by the way, those 40 went fast—despite their daunting, tome-like size and heft, a side effect of those extended illo-only sections, Selznick's page-turners are surprisingly quick reads.) The author uses his two modes of narration to alternate between two deaf children in different time periods (the 1920s and 1970s) whose lives are mysteriously connected by a wolf diorama at New York's American Museum of Natural History, again expertly weaving real places and events (the 1977 NYC blackout, for example) into his story. And the almost cinematic nature of the illustrated sections retains loses none of its power here: The illustration in which the two stories come together, and we see the 1970s boy's face in an illustration for the first time, packs an incredible emotional punch that literally brought tears to my eyes.

Now, I will admit that by setting his story at this particular museum, and also using the amazing New York City panorama at the Queens Museum of Art as a key location for a vital moment of his story, Selznick had this Upper West Side–raised boy at hello. (There are also several knowing and most pleasing nods to the mother of all museum-based children's books, E. L. Konigsburg's From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.) Nonetheless, I'm confident that even those less steeped in NYC nostalgia than I am will enjoy Wonderstruck as much as I did. Which is quite a lot.

And in future, I will refrain from doubting Selznick's storytelling technique—and just enjoy it.

[Cover image courtesy of Scholastic]

November 3, 2011

New Books: Novels for Older Kids III

Once again I turn to Elizabeth, my 13-year-old colleague, for some of her favorite new tween and young-adult novels of the last year or so. (None are very new in hardcover at this point, but on the bright side, many are just coming out in paperback!) Without further ado:

Bloodline Rising, by Katy Moran. Written more as a "companion" than a sequel to Moran's earlier British Dark Ages tale Bloodline, this novel tells the story of Cai, a clever young thief in seventh-century Constantinople. With his father away at war, he is betrayed by a rival and sold as a slave to a ship heading north, to Britain—which happens to be where his parents come from. He is taken in by a lord who clearly knew his parents and put to work as a spy amid major political intrigue...but soon finds that the man who took him in may have had something to do with his parents' departure from Britain.

Elizabeth's take: This book was suspenseful and had complex, believable characters. I couldn't put it down and could barely believe the twist in the ending! I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys stories full of danger, tension, and action.

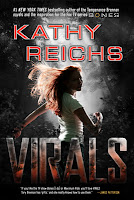

Virals, by Kathy Reich. The first work for young readers by this forensic anthropologist, the novelist behind the TV series Bones, and the initial entry in a new sci-fi/suspense series, Virals is about 14-year-old Tory (she's the niece of Temperance Brennan, the character played by Emily Deschanel on the TV show), who must go live with the marine-biologist father she's never known on a small South Carolina island after her mother is killed in an accident. She soon finds a similarly scientific-minded group of kids to hang out with, and before long they've noticed something strange about the nearby Loggerhead Research Institute. But after they rescue a wolf-dog puppy from the laboratory, they're exposed to a canine virus that changes their DNA, heightening their senses and reflexes—which turns out to come in handy, since they end up with a cold-case murder on their hands.

Elizabeth's take: This sci-fi mystery was amazing! The action and creepy science projects kept me engrossed from beginning to end. I've already recommended this book to several of my friends.

The Eternal Ones, by Kirsten Miller. Tennessee teenager Haven has always had visions of a past life, in which she was a girl named Constance whose doomed love for a boy named Ethan ended in disaster and death. But when she sees tabloid-TV coverage of an infamous celebrity named Iain Morrow, she is certain that she recognizes Ethan, and so when she turns 18 she heads up to New York City to find him. She finds that Iain feels their connection as well, and a love affair soon begins between the two...but soon Haven has doubts: Is Iain really Ethan, or could he be the person behind the deaths of Constance and Ethan in that past existence? Enlisting the help of a secret society with knowledge of reincarnation, Haven determines to find out the truth without reliving every detail of Constance's past.

Elizabeth's take: I loved this book! It was impossible to put down once I'd started. The author keeps you guessing constantly about the characters, their motives, and their intentions. The plot twists and bittersweet ending make it one of my favorite books.

Mockingbird, by Kathryn Erskine. This winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Young Readers is about Caitlin, a 10-year-old girl with Asperger's syndrome whose older brother has been killed in a school shooting. Told with remarkable sensitivity and insight from Caitlin's own perspective, it takes the reader through her attempt to deal with the tragedy herself, and to help her devastated father to weather the grief as well.

Elizabeth's take: This book was really touching, and offered an interesting point of view. It is refreshing to see things from the perspective of a person who doesn't view things the same way as most people.

[Cover images courtesy of Candlewick Press (Bloodline Rising) and Penguin USA (others).]

Bloodline Rising, by Katy Moran. Written more as a "companion" than a sequel to Moran's earlier British Dark Ages tale Bloodline, this novel tells the story of Cai, a clever young thief in seventh-century Constantinople. With his father away at war, he is betrayed by a rival and sold as a slave to a ship heading north, to Britain—which happens to be where his parents come from. He is taken in by a lord who clearly knew his parents and put to work as a spy amid major political intrigue...but soon finds that the man who took him in may have had something to do with his parents' departure from Britain.

Elizabeth's take: This book was suspenseful and had complex, believable characters. I couldn't put it down and could barely believe the twist in the ending! I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys stories full of danger, tension, and action.

Virals, by Kathy Reich. The first work for young readers by this forensic anthropologist, the novelist behind the TV series Bones, and the initial entry in a new sci-fi/suspense series, Virals is about 14-year-old Tory (she's the niece of Temperance Brennan, the character played by Emily Deschanel on the TV show), who must go live with the marine-biologist father she's never known on a small South Carolina island after her mother is killed in an accident. She soon finds a similarly scientific-minded group of kids to hang out with, and before long they've noticed something strange about the nearby Loggerhead Research Institute. But after they rescue a wolf-dog puppy from the laboratory, they're exposed to a canine virus that changes their DNA, heightening their senses and reflexes—which turns out to come in handy, since they end up with a cold-case murder on their hands.

Elizabeth's take: This sci-fi mystery was amazing! The action and creepy science projects kept me engrossed from beginning to end. I've already recommended this book to several of my friends.

The Eternal Ones, by Kirsten Miller. Tennessee teenager Haven has always had visions of a past life, in which she was a girl named Constance whose doomed love for a boy named Ethan ended in disaster and death. But when she sees tabloid-TV coverage of an infamous celebrity named Iain Morrow, she is certain that she recognizes Ethan, and so when she turns 18 she heads up to New York City to find him. She finds that Iain feels their connection as well, and a love affair soon begins between the two...but soon Haven has doubts: Is Iain really Ethan, or could he be the person behind the deaths of Constance and Ethan in that past existence? Enlisting the help of a secret society with knowledge of reincarnation, Haven determines to find out the truth without reliving every detail of Constance's past.

Elizabeth's take: I loved this book! It was impossible to put down once I'd started. The author keeps you guessing constantly about the characters, their motives, and their intentions. The plot twists and bittersweet ending make it one of my favorite books.

Mockingbird, by Kathryn Erskine. This winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Young Readers is about Caitlin, a 10-year-old girl with Asperger's syndrome whose older brother has been killed in a school shooting. Told with remarkable sensitivity and insight from Caitlin's own perspective, it takes the reader through her attempt to deal with the tragedy herself, and to help her devastated father to weather the grief as well.

Elizabeth's take: This book was really touching, and offered an interesting point of view. It is refreshing to see things from the perspective of a person who doesn't view things the same way as most people.

[Cover images courtesy of Candlewick Press (Bloodline Rising) and Penguin USA (others).]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)