Like so many people my age, I was raised on the Beatles—I think I took either my mother or father's copy of Magical Mystery Tour to my preschool show-and-tell once. (What precisely I said about it is, rather fortunately, lost to my memory.)

But while the Fab Four's music had become a fairly natural background to my own early parenting years as well, I hadn't given the animated film Yellow Submarine a lot of thought. (I seem to recall that my snobbish elementary-school self largely dismissed the movie after my first viewing, upon realizing that the real Beatles hadn't done their own voices.)

Until, that is, a trip to London when our oldest was three, and happened to be obsessed with "All You Need Is Love"—having run through the picture books we had brought with us, we grabbed an edition of the book version of Yellow Submarine, which features all the colorful Heinz Edelmann graphics of the film, if none of the actual music. It was a huge hit with Dash, and has been a favorite book of his and his younger brother's ever since.

And now, I discover, iTunes is offering an iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch edition of Yellow Submarine—completely free of charge! (OK, the iPad's not free by any means, I grant you.) It makes smart, efficient use of the opportunities for interactivity—at a touch, the butterflies flutter, the Blue Meanies laugh evilly, and the Beatles themselves pop up and down in the Sea of Holes. Plus, there's a whole slew of video clips from the movie on just about every page, which means that in this edition, you do get some of the original songs. (Naturally, there's a page at the end where you can buy any or all of them on iTunes.)

Maybe it's just the relative newness, still, of interactive books on tablets, but when I unveiled this surprise for Dash and Griff, they were mesmerized and delighted (and—fair warning—wouldn't let me have my iPad back). Kinda wishing now that I'd saved it as a (free!) Christmas present...

[Image © Apple Corps Ltd., courtesy of PR Newswire]

December 19, 2011

December 14, 2011

Security Blanket: The Lump of Coal

I'm generally not much for holiday-themed children's books, which are often as uninspired and gimmicky as the impulse-buy specials for adults that you find by the Barnes & Noble cashiers this time of year. But if there were going to be an exception, it should come as no surprise that it would be a holiday-themed children's book by Lemony Snicket, perhaps the author best suited to taking the treacle out of traditionally tacky subject matter.

The title itself hints at this, but The Lump of Coal is more than just a one-liner—in it, Snicket manages to eat his cake and have it, doubling back on his seeming cynicism. Its protagonist is, yes, the titular lump, who wears a tuxedo and wants to be an artist, but is dismayed to find that the art gallery displaying coal art is not seeking works by actual anthropomorphic coal chunks.

He is similarly unsuccessful when trying to find a position fueling a Korean barbecue, and about to despair when he runs across a man dressed as Santa—who has a naughty son, and, accordingly, a fitting job for a piece of coal like our hero. Then, just when you think the book is merely a breezy, witty take on bad kids' getting their comeuppance, Snicket takes a sharp turn to a happy and most unexpected ending, which I won't spoil here.

The Lump of Coal, which also features expressive illustrations by Brett Helquist, has been a favorite of mine and my wife's for a few years now, but this Christmas season our three-year-old, Griffin, has taken a strong shine to it as well—an indication that Snicket’s sophisticated humor is by no means beyond the understanding of those just learning to read. Truly, then, a Christmas book for all ages, in the best sense.

[Cover image courtesy of HarperCollins]

The title itself hints at this, but The Lump of Coal is more than just a one-liner—in it, Snicket manages to eat his cake and have it, doubling back on his seeming cynicism. Its protagonist is, yes, the titular lump, who wears a tuxedo and wants to be an artist, but is dismayed to find that the art gallery displaying coal art is not seeking works by actual anthropomorphic coal chunks.

He is similarly unsuccessful when trying to find a position fueling a Korean barbecue, and about to despair when he runs across a man dressed as Santa—who has a naughty son, and, accordingly, a fitting job for a piece of coal like our hero. Then, just when you think the book is merely a breezy, witty take on bad kids' getting their comeuppance, Snicket takes a sharp turn to a happy and most unexpected ending, which I won't spoil here.

The Lump of Coal, which also features expressive illustrations by Brett Helquist, has been a favorite of mine and my wife's for a few years now, but this Christmas season our three-year-old, Griffin, has taken a strong shine to it as well—an indication that Snicket’s sophisticated humor is by no means beyond the understanding of those just learning to read. Truly, then, a Christmas book for all ages, in the best sense.

[Cover image courtesy of HarperCollins]

December 11, 2011

New Music: Celtic Christmas

Putumayo's compilations of children's music are such reliable standbys in the genre, so consistently good, that I end up never writing about them. I realize that doesn't sound as if it makes any sense, but it does: It's not because I take them for granted, exactly, but because I have this feeling everyone knows about them already. So in my mind, it's as if I were recommending this really great toy called Legos.

This, however, is not only not fair, it's not true. As I can still recall (when I try) from the days before I began covering kids' entertainment, it's entirely possible in the whirlwind that is being a parent to know about precisely nothing that came out after one's own childhood.

So let me take advantage of the approaching Christmas season to point out Putumayo's latest output, Celtic Christmas, a collection of 11 traditional Yuletide carols in, yes, Celtic renditions that range from peppy and energetic (David Huntsinger's take on "Angels We Have Heard on High") to dreamy and pensive (the French carol "Noel Nouvelet," beautifully performed by the only-seemingly-named-by-Jack-Black group DruidStone; my three-year-old insists on putting this track on repeat every time he hears it). There's even a Gaelic rendition of "White Christmas," aptly enough sung by Lasaidfhíona Ní Chonaola. Like just about every Putumayo kids' collection I've heard, Celtic Christmas is suitably atmospheric—in this case setting the perfect seasonal tone—while also featuring top-notch musicians throughout.

[Cover image courtesy of Putumayo]

This, however, is not only not fair, it's not true. As I can still recall (when I try) from the days before I began covering kids' entertainment, it's entirely possible in the whirlwind that is being a parent to know about precisely nothing that came out after one's own childhood.

So let me take advantage of the approaching Christmas season to point out Putumayo's latest output, Celtic Christmas, a collection of 11 traditional Yuletide carols in, yes, Celtic renditions that range from peppy and energetic (David Huntsinger's take on "Angels We Have Heard on High") to dreamy and pensive (the French carol "Noel Nouvelet," beautifully performed by the only-seemingly-named-by-Jack-Black group DruidStone; my three-year-old insists on putting this track on repeat every time he hears it). There's even a Gaelic rendition of "White Christmas," aptly enough sung by Lasaidfhíona Ní Chonaola. Like just about every Putumayo kids' collection I've heard, Celtic Christmas is suitably atmospheric—in this case setting the perfect seasonal tone—while also featuring top-notch musicians throughout.

[Cover image courtesy of Putumayo]

December 7, 2011

New Books: E-mergency

When you talk about letter books, you usually mean ABC books, a genre for very young kids that could probably keep the board-book publishing industry in business all by itself. E-mergency!, however, is a letter book for somewhat older children, with a plot and a lesson beyond the basics of what in the alphabet goes where.

Its premise is that all the letters, from A to Z, live together in a big house. When E trips on the stairs one day and is injured, it's determined that she needs a bit of R&R to recover, so O steps in for her in all her words—with confusing results that will be particularly funny to elementary-school kids with the alphabet firmly under their belts. (Part of the fun—as well as the book's educational point—is that this couldn't have happened to a more important letter, since, as a nifty chart on the book's last page shows, E is by far the most frequently used letter in the English language, as well as many others.)

The book, full of clever wordplay (letter-play?) in multiple asides on every page, is all the more astounding for being the brainchild of 14-year-old Ezra Fields-Meyer, whose was diagnosed with high-functioning autism as a toddler. His short animated video "Alphabet House" (shown below) came to the attention of veteran children's-book illustrator Tom Lichtenheld, who loved the concept and adapted it. The end product does stand out among the work of writers many mulitiples of Fields-Meyer's age—for being better than a good portion of it.

[Cover image courtesy of Chronicle Books]

Its premise is that all the letters, from A to Z, live together in a big house. When E trips on the stairs one day and is injured, it's determined that she needs a bit of R&R to recover, so O steps in for her in all her words—with confusing results that will be particularly funny to elementary-school kids with the alphabet firmly under their belts. (Part of the fun—as well as the book's educational point—is that this couldn't have happened to a more important letter, since, as a nifty chart on the book's last page shows, E is by far the most frequently used letter in the English language, as well as many others.)

The book, full of clever wordplay (letter-play?) in multiple asides on every page, is all the more astounding for being the brainchild of 14-year-old Ezra Fields-Meyer, whose was diagnosed with high-functioning autism as a toddler. His short animated video "Alphabet House" (shown below) came to the attention of veteran children's-book illustrator Tom Lichtenheld, who loved the concept and adapted it. The end product does stand out among the work of writers many mulitiples of Fields-Meyer's age—for being better than a good portion of it.

[Cover image courtesy of Chronicle Books]

December 3, 2011

New Books: Around the World

Graphic novels have gained a great deal of respectability since I was a kid. With the possible exception of Herge's Tintin books—and those had European cred!—back then, the genre was linked more with its cousin, the comic book, than with other children's books. And comic books were distinctly not respectable in a literary sense: Even the brilliant, complex 1980s and '90s work of Neil Gaiman, Frank Miller, and Alan Moore (most of which is by no means for children, I hasten to say) had a bit of a discriminatory hurdle to get over before being taken seriously by the mainstream.

Today, major publishers have full graphic-novel (and even comic-book!) divisions, turning out excellent work for both kids and adults that covers nearly every genre and field. To my delight, there are even nonfiction graphic novels, whose leading practitioner would now have to be Matt Phelan. His latest book, Around the World, tells the story of three amazing, adventurous, and absolutely real 19th-century solo global circumnavigations: Thomas Stevens's 1884 journey via large-wheel bicycle, Nellie Bly's 1889 newspaper-sponsored race to surpass Jules Verne's fictional 80-day achievement, and Joshua Slocum's 1895 small-boat trip.

These are the sorts of stories that have long turned up in nonfiction children's books, and I remember reading about Bly's race against time in one myself as a child—which makes it all the more remarkable that Phelan has turned up the relatively undiscovered of Stevens and Slocum, neither of whose names were the least bit familiar to me. All three stories are remarkable, the kind that feel incredibly improbable for their time (especially Slocum's, which seems downright impossible).

And as he proved in the historical-fiction work The Storm in the Barn, Phelan knows what to do with a good story. His accounts of the three journeys move from panel to panel like a well-edited film, and he has the ability able to capture and denote his protagonists' characteristics with a lightly illustrated expression, much as a great film actor can express an emotion in a glance.

The author is also thoughtful enough to move past the actions of the three adventurers to the question of why each is pursuing his or her goal—a question that goes a long way to establishing character and, not coincidentally, to making Phelan's book a lot more interesting than most children's nonfiction, including the similarly themed books I read as a kid. Maybe it's redundant to call a graphic novel a page-turner, but that's the term that comes to mind when I think about how eagerly my seven-year-old reads it.

[Cover image courtesy of Candlewick Press]

Today, major publishers have full graphic-novel (and even comic-book!) divisions, turning out excellent work for both kids and adults that covers nearly every genre and field. To my delight, there are even nonfiction graphic novels, whose leading practitioner would now have to be Matt Phelan. His latest book, Around the World, tells the story of three amazing, adventurous, and absolutely real 19th-century solo global circumnavigations: Thomas Stevens's 1884 journey via large-wheel bicycle, Nellie Bly's 1889 newspaper-sponsored race to surpass Jules Verne's fictional 80-day achievement, and Joshua Slocum's 1895 small-boat trip.

These are the sorts of stories that have long turned up in nonfiction children's books, and I remember reading about Bly's race against time in one myself as a child—which makes it all the more remarkable that Phelan has turned up the relatively undiscovered of Stevens and Slocum, neither of whose names were the least bit familiar to me. All three stories are remarkable, the kind that feel incredibly improbable for their time (especially Slocum's, which seems downright impossible).

And as he proved in the historical-fiction work The Storm in the Barn, Phelan knows what to do with a good story. His accounts of the three journeys move from panel to panel like a well-edited film, and he has the ability able to capture and denote his protagonists' characteristics with a lightly illustrated expression, much as a great film actor can express an emotion in a glance.

The author is also thoughtful enough to move past the actions of the three adventurers to the question of why each is pursuing his or her goal—a question that goes a long way to establishing character and, not coincidentally, to making Phelan's book a lot more interesting than most children's nonfiction, including the similarly themed books I read as a kid. Maybe it's redundant to call a graphic novel a page-turner, but that's the term that comes to mind when I think about how eagerly my seven-year-old reads it.

[Cover image courtesy of Candlewick Press]

November 30, 2011

Fids & Kamily Music Awards

I'm a little late to the party, but in case anyone missed it, I wanted to point out the winners of the 2011 Fids & Kamily Music Awards, which were announced back on November 19th. Many of my own favorite albums of the past year made the list. (I'm flattered to be among the voters, so that's not entirely a coincidence—though it's nice to see I'm not alone in my appreciation of Recess Monkey, Frances England, Lunch Money, and the rest!)

Anyway, if you're looking for some good kids' music for year's end—whether you're after the latest from a big name like Dan Zanes or a gem from an artist you didn't know before—this list is an excellent place to start.

Anyway, if you're looking for some good kids' music for year's end—whether you're after the latest from a big name like Dan Zanes or a gem from an artist you didn't know before—this list is an excellent place to start.

November 29, 2011

New Movies: Hugo

As huge fans of Brian Selznick's book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, our family was very interested in the film version. Its director, Martin Scorsese, seemed a great fit for a story so steeped in the early days of moviemaking, so my usual low expectations for adaptations of beloved books were not quite so tempered. We rushed out to see it the day after Thanksgiving. (The boys, of course, were thrilled beyond belief, as they continue to be every time we actually go to a movie theater. It's one of those lovely things to watch that I know won't last forever, or perhaps even much longer.)

The film version of Hugo Cabret, as its shortened title—just Hugo—might imply, has had its story pared down and streamlined. Lovers of the book should be prepared for less depth, complexity, and just plain time given to its main storyline of a orphaned boy who lives in the walls of a Paris train station between the world wars, continuing his vanished uncle's job of keeping the station's many clocks running, and meanwhile trying to repair a complicated mechanical toy that represents, to him, his deceased father.

The movie zips through most of this—Jude Law, as Hugo's father, and Ray Winstone, as the uncle, have essentially just a scene apiece, though both manage to make remarkably strong impressions—to get to the part that, I imagine, is what drew Scorsese to direct the film: Hugo's interactions with the proprietor of a toy shop in the train station. This man turns out to be Georges Méliès, one of the first great directors of movies that told stories (as opposed to merely capturing true-life events on film).

And while it's fair to say that Hugo, perhaps inevitably, falls a bit short of its source material in terms of its main character's own story, when it comes to the Méliès stuff, it is able to exceed it. What were just images in Selznick's book—a still from Harold Lloyd's classic Safety Last!, as well as many from Méliès' own charmingly trippy films—come to life in the film as the full-blown cinema they are. And we couldn't be in better hands for this kind of thing. Scorsese has always been fond of magically capturing real historical events and references in his films—his re-creation of a famous Jacob Riis photograph in Gangs of New York comes to mind—and in Hugo, with the history of film itself to draw on, his excitement is contagious; when Scorsese portrays the excitement and the energy of Méliès's original shoots, we share in Scorsese's (and Méliès's) delight.

Of course, such excitement requires knowledge of the history itself, which means this aspect of the film—probably its best—is more or less lost on the kids. (Though I think Dash, our seven-year-old, got some of the wonder—Méliès' films are pretty magical, after all, outside of any historical context, or they wouldn't have been as popular as they were in their own time.) Happily, even the cut-down version of Selznick's story is engaging enough to keep most youngsters fully engaged; I’d say any child who’s able to fully process the book should have a great time. (In other words, as we should have realized it would be, the two-hour length was a bit much for our three-year-old.)

A great deal of the credit must be given to the actors, who fill out a screenplay that occasionally feels thin—particularly the two leads. Ben Kingsley is ideal as Méliès, able to convey the emotion of this wounded old man with a glance, and Asa Butterfield is a revelation (at least to those, like me, who didn't see him in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , I guess), capturing Hugo's desperation movingly. We found the rest of the cast equally admirable, mostly in roles that the film has built up significantly from the book, presumably in an attempt to lighten things up a bit. (The lone exception, surprisingly, was the ubiquitous Chloë Moretz in the key role of Méliès's niece, Isabelle, whose performance we found forced and even irritating at times.)

, I guess), capturing Hugo's desperation movingly. We found the rest of the cast equally admirable, mostly in roles that the film has built up significantly from the book, presumably in an attempt to lighten things up a bit. (The lone exception, surprisingly, was the ubiquitous Chloë Moretz in the key role of Méliès's niece, Isabelle, whose performance we found forced and even irritating at times.)

So no, Hugo doesn't deliver all the same joys the book did, falling well short of it in some ways. But it also manages to exceed its source in others, and that makes it a very enjoyable family movie. (I think many adults without young children will even find it so; I’m also very curious to know what those without prior exposure to Selznick's book think of the film.)

One last thing: 3D. Like so many movies these days, Hugo was shot in it. While I can see Scorsese figuring that Georges Méliès himself would have found modern 3D film technology pretty damn cool, I have to say that in the end, I didn't really see the point. The effect is certainly remarkable, a vast improvement on earlier, more primitive attempts at 3D moviemaking. But after the first five or ten minutes of "OK, that's pretty amazing," I found that I alternated between forgetting about it and, worse, finding it a distraction from the story. Maybe it’s yet another sign I’m getting old, but I think I'd opt for the 2D version—in fact, I’m seriously considering going back for a second screening in less-distracting 2D.

[Image © 2011 Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.]

The film version of Hugo Cabret, as its shortened title—just Hugo—might imply, has had its story pared down and streamlined. Lovers of the book should be prepared for less depth, complexity, and just plain time given to its main storyline of a orphaned boy who lives in the walls of a Paris train station between the world wars, continuing his vanished uncle's job of keeping the station's many clocks running, and meanwhile trying to repair a complicated mechanical toy that represents, to him, his deceased father.

The movie zips through most of this—Jude Law, as Hugo's father, and Ray Winstone, as the uncle, have essentially just a scene apiece, though both manage to make remarkably strong impressions—to get to the part that, I imagine, is what drew Scorsese to direct the film: Hugo's interactions with the proprietor of a toy shop in the train station. This man turns out to be Georges Méliès, one of the first great directors of movies that told stories (as opposed to merely capturing true-life events on film).

And while it's fair to say that Hugo, perhaps inevitably, falls a bit short of its source material in terms of its main character's own story, when it comes to the Méliès stuff, it is able to exceed it. What were just images in Selznick's book—a still from Harold Lloyd's classic Safety Last!, as well as many from Méliès' own charmingly trippy films—come to life in the film as the full-blown cinema they are. And we couldn't be in better hands for this kind of thing. Scorsese has always been fond of magically capturing real historical events and references in his films—his re-creation of a famous Jacob Riis photograph in Gangs of New York comes to mind—and in Hugo, with the history of film itself to draw on, his excitement is contagious; when Scorsese portrays the excitement and the energy of Méliès's original shoots, we share in Scorsese's (and Méliès's) delight.

Of course, such excitement requires knowledge of the history itself, which means this aspect of the film—probably its best—is more or less lost on the kids. (Though I think Dash, our seven-year-old, got some of the wonder—Méliès' films are pretty magical, after all, outside of any historical context, or they wouldn't have been as popular as they were in their own time.) Happily, even the cut-down version of Selznick's story is engaging enough to keep most youngsters fully engaged; I’d say any child who’s able to fully process the book should have a great time. (In other words, as we should have realized it would be, the two-hour length was a bit much for our three-year-old.)

A great deal of the credit must be given to the actors, who fill out a screenplay that occasionally feels thin—particularly the two leads. Ben Kingsley is ideal as Méliès, able to convey the emotion of this wounded old man with a glance, and Asa Butterfield is a revelation (at least to those, like me, who didn't see him in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

So no, Hugo doesn't deliver all the same joys the book did, falling well short of it in some ways. But it also manages to exceed its source in others, and that makes it a very enjoyable family movie. (I think many adults without young children will even find it so; I’m also very curious to know what those without prior exposure to Selznick's book think of the film.)

One last thing: 3D. Like so many movies these days, Hugo was shot in it. While I can see Scorsese figuring that Georges Méliès himself would have found modern 3D film technology pretty damn cool, I have to say that in the end, I didn't really see the point. The effect is certainly remarkable, a vast improvement on earlier, more primitive attempts at 3D moviemaking. But after the first five or ten minutes of "OK, that's pretty amazing," I found that I alternated between forgetting about it and, worse, finding it a distraction from the story. Maybe it’s yet another sign I’m getting old, but I think I'd opt for the 2D version—in fact, I’m seriously considering going back for a second screening in less-distracting 2D.

[Image © 2011 Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.]

November 18, 2011

New Books: A Dog Is a Dog

Picture books for the youngest readers can be many things—beautiful, moving, offbeat. But sometimes children (and their parents, too) are just looking for something, well, silly. Satisfying this common craving is Stephen Shaskan's new A Dog Is a Dog, a series of rhyming couplets illustrated in a pleasantly upbeat faux-retro style.

The book begins as if it's going to be merely about the various canine attributes. Until, that is, we get to the end of the first set of couplets—"A dog is a dog, unless it's...a cat!"—at which point the dog who'd been romping around the previous pages unzips himself to reveal that he's really a cat in a dog suit. (If you keep the premise from them, young kids will find this moment both truly shocking and hilariously funny; they may even need to pause before proceeding.)

From there, of course, we get more sets of couplets followed by more costume unzippings, which my little ones met with mounting hysteria. I won't give away the full menagerie here, but suffice it to say that a squid is involved at one point, before Shaskan neatly wraps things up by bringing back where we started. There's nothing terribly deep going on in A Dog Is a Dog—it's just very successful at being very silly indeed, in a novel way. And when that's what you and your kids are after, there's nothing more you could need from a picture book.

[Photo: Whitney Webster]

The book begins as if it's going to be merely about the various canine attributes. Until, that is, we get to the end of the first set of couplets—"A dog is a dog, unless it's...a cat!"—at which point the dog who'd been romping around the previous pages unzips himself to reveal that he's really a cat in a dog suit. (If you keep the premise from them, young kids will find this moment both truly shocking and hilariously funny; they may even need to pause before proceeding.)

From there, of course, we get more sets of couplets followed by more costume unzippings, which my little ones met with mounting hysteria. I won't give away the full menagerie here, but suffice it to say that a squid is involved at one point, before Shaskan neatly wraps things up by bringing back where we started. There's nothing terribly deep going on in A Dog Is a Dog—it's just very successful at being very silly indeed, in a novel way. And when that's what you and your kids are after, there's nothing more you could need from a picture book.

[Photo: Whitney Webster]

Labels:

children's books,

kids' books,

new books,

picture books,

Stephen Shaskan

November 16, 2011

New Books: The Cheshire Cheese Cat

In their new chapter book, The Cheshire Cheese Cat, Carmen Agra Deedy and Randall Wright put a couple of twists on the old "what if a cat and a mouse became friends?" trope (a favorite of mine ever since I first came across The Cricket in Times Square).

The first is that their cat protagonist, Skilley enters into a relationship with Pip, the mouse, initially as a business proposition: To get off the streets of Victorian London, he has become a mouser in a particularly infested pub. There's one problem, though: He doesn't eat mice—he prefers cheese. So he and the mice, represented by Pip, form a pact: He will catch them when in view of humans, then let them go when not. In return, the mice will give him ample portions of the pub's own delectable and proprietary cheese (which is stored in a place the mice can get to but cats cannot).

All is going swimmingly until another alley cat who does have the usual taste for mouse flesh enters the mix, and Skilley must find a way to protect his new friends. Complicating matters further is the presence of a grumpy, marooned raven in the pub's attic, whose absence from his Tower of London home, through a series of misunderstandings, risks becoming a reason for a full-scale war between England and France.

The second twist is that the pub in question happens to be the haunt of several of London's best writers, including Wilkie Collins, William Thackeray, and Charles Dickens, to the last of which this entire book is an homage. Dickens is having a bit of writer's block over the opening of his new novel about the French Revolution, and the goings-on at the pub prove to be a welcome distraction for him. In the end, the famous writer, the cat, and the mouse are able to do one another good turns, one of which has a monumental impact on literary history.

The Cheshire Cheese Cat, which also features illustrations by the formidable Barry Moser, is perfect in tone and spirit for young chapter-book readers, with enough adventure and plot twists to keep interest levels high without ever veering into anything truly upsetting or scary. It also may serve as an introduction to the work of Dickens himself, whose books are among the most accesible of adult classics to literary-minded kids. (If you're heading in that direction, by the way, I'd recommend starting with audiobooks, in which Dickens's intoxicating use of language comes across well—or, for the approaching season, A Christmas Carol. Or both!)

[Cover image courtesy of Peachtree Publishers]

The first is that their cat protagonist, Skilley enters into a relationship with Pip, the mouse, initially as a business proposition: To get off the streets of Victorian London, he has become a mouser in a particularly infested pub. There's one problem, though: He doesn't eat mice—he prefers cheese. So he and the mice, represented by Pip, form a pact: He will catch them when in view of humans, then let them go when not. In return, the mice will give him ample portions of the pub's own delectable and proprietary cheese (which is stored in a place the mice can get to but cats cannot).

All is going swimmingly until another alley cat who does have the usual taste for mouse flesh enters the mix, and Skilley must find a way to protect his new friends. Complicating matters further is the presence of a grumpy, marooned raven in the pub's attic, whose absence from his Tower of London home, through a series of misunderstandings, risks becoming a reason for a full-scale war between England and France.

The second twist is that the pub in question happens to be the haunt of several of London's best writers, including Wilkie Collins, William Thackeray, and Charles Dickens, to the last of which this entire book is an homage. Dickens is having a bit of writer's block over the opening of his new novel about the French Revolution, and the goings-on at the pub prove to be a welcome distraction for him. In the end, the famous writer, the cat, and the mouse are able to do one another good turns, one of which has a monumental impact on literary history.

The Cheshire Cheese Cat, which also features illustrations by the formidable Barry Moser, is perfect in tone and spirit for young chapter-book readers, with enough adventure and plot twists to keep interest levels high without ever veering into anything truly upsetting or scary. It also may serve as an introduction to the work of Dickens himself, whose books are among the most accesible of adult classics to literary-minded kids. (If you're heading in that direction, by the way, I'd recommend starting with audiobooks, in which Dickens's intoxicating use of language comes across well—or, for the approaching season, A Christmas Carol. Or both!)

[Cover image courtesy of Peachtree Publishers]

November 11, 2011

New Books: Wonder Struck

Brian Selznick's 2007 children's book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, followed the path of every author's fantasy: It got magnificent reviews full of words like groundbreaking; it won a Caldecott; it became that book every parent tells every other parent about; and—just to make sure Selznick would be pinching himself—now it's a major motion picture directed by Martin Scorsese. Not bad for his first time out there! Selznick deserved every bit of it, too; Hugo Cabret is marvelous. (If you and your kids haven't read it, I highly recommend it, as does a fellow critic somewhat closer to the intended audience.)

Still, being an inveterate worrier, I wondered how Selznick would follow up on his blaze of glory. The key innovation of Hugo Cabret—in what's otherwise a traditional chapter book, the author inserts ten-to-twenty-page sections in which the narrative is moved along purely through illustrations—seemed almost custom-made, in its cinematic nature, for that book's cinema-themed story. When I saw that Selznick's new book, Wonderstruck, would indeed use the same technique, I wondered if it would work as splendidly the second time around. Might it even start to feel gimmicky, more a narrative crutch than the revelation it had been originally?

About 40 pages into Wonderstruck, I stopped worrying. (And by the way, those 40 went fast—despite their daunting, tome-like size and heft, a side effect of those extended illo-only sections, Selznick's page-turners are surprisingly quick reads.) The author uses his two modes of narration to alternate between two deaf children in different time periods (the 1920s and 1970s) whose lives are mysteriously connected by a wolf diorama at New York's American Museum of Natural History, again expertly weaving real places and events (the 1977 NYC blackout, for example) into his story. And the almost cinematic nature of the illustrated sections retains loses none of its power here: The illustration in which the two stories come together, and we see the 1970s boy's face in an illustration for the first time, packs an incredible emotional punch that literally brought tears to my eyes.

Now, I will admit that by setting his story at this particular museum, and also using the amazing New York City panorama at the Queens Museum of Art as a key location for a vital moment of his story, Selznick had this Upper West Side–raised boy at hello. (There are also several knowing and most pleasing nods to the mother of all museum-based children's books, E. L. Konigsburg's From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.) Nonetheless, I'm confident that even those less steeped in NYC nostalgia than I am will enjoy Wonderstruck as much as I did. Which is quite a lot.

And in future, I will refrain from doubting Selznick's storytelling technique—and just enjoy it.

[Cover image courtesy of Scholastic]

Still, being an inveterate worrier, I wondered how Selznick would follow up on his blaze of glory. The key innovation of Hugo Cabret—in what's otherwise a traditional chapter book, the author inserts ten-to-twenty-page sections in which the narrative is moved along purely through illustrations—seemed almost custom-made, in its cinematic nature, for that book's cinema-themed story. When I saw that Selznick's new book, Wonderstruck, would indeed use the same technique, I wondered if it would work as splendidly the second time around. Might it even start to feel gimmicky, more a narrative crutch than the revelation it had been originally?

About 40 pages into Wonderstruck, I stopped worrying. (And by the way, those 40 went fast—despite their daunting, tome-like size and heft, a side effect of those extended illo-only sections, Selznick's page-turners are surprisingly quick reads.) The author uses his two modes of narration to alternate between two deaf children in different time periods (the 1920s and 1970s) whose lives are mysteriously connected by a wolf diorama at New York's American Museum of Natural History, again expertly weaving real places and events (the 1977 NYC blackout, for example) into his story. And the almost cinematic nature of the illustrated sections retains loses none of its power here: The illustration in which the two stories come together, and we see the 1970s boy's face in an illustration for the first time, packs an incredible emotional punch that literally brought tears to my eyes.

Now, I will admit that by setting his story at this particular museum, and also using the amazing New York City panorama at the Queens Museum of Art as a key location for a vital moment of his story, Selznick had this Upper West Side–raised boy at hello. (There are also several knowing and most pleasing nods to the mother of all museum-based children's books, E. L. Konigsburg's From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.) Nonetheless, I'm confident that even those less steeped in NYC nostalgia than I am will enjoy Wonderstruck as much as I did. Which is quite a lot.

And in future, I will refrain from doubting Selznick's storytelling technique—and just enjoy it.

[Cover image courtesy of Scholastic]

November 3, 2011

New Books: Novels for Older Kids III

Once again I turn to Elizabeth, my 13-year-old colleague, for some of her favorite new tween and young-adult novels of the last year or so. (None are very new in hardcover at this point, but on the bright side, many are just coming out in paperback!) Without further ado:

Bloodline Rising, by Katy Moran. Written more as a "companion" than a sequel to Moran's earlier British Dark Ages tale Bloodline, this novel tells the story of Cai, a clever young thief in seventh-century Constantinople. With his father away at war, he is betrayed by a rival and sold as a slave to a ship heading north, to Britain—which happens to be where his parents come from. He is taken in by a lord who clearly knew his parents and put to work as a spy amid major political intrigue...but soon finds that the man who took him in may have had something to do with his parents' departure from Britain.

Elizabeth's take: This book was suspenseful and had complex, believable characters. I couldn't put it down and could barely believe the twist in the ending! I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys stories full of danger, tension, and action.

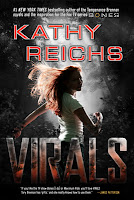

Virals, by Kathy Reich. The first work for young readers by this forensic anthropologist, the novelist behind the TV series Bones, and the initial entry in a new sci-fi/suspense series, Virals is about 14-year-old Tory (she's the niece of Temperance Brennan, the character played by Emily Deschanel on the TV show), who must go live with the marine-biologist father she's never known on a small South Carolina island after her mother is killed in an accident. She soon finds a similarly scientific-minded group of kids to hang out with, and before long they've noticed something strange about the nearby Loggerhead Research Institute. But after they rescue a wolf-dog puppy from the laboratory, they're exposed to a canine virus that changes their DNA, heightening their senses and reflexes—which turns out to come in handy, since they end up with a cold-case murder on their hands.

Elizabeth's take: This sci-fi mystery was amazing! The action and creepy science projects kept me engrossed from beginning to end. I've already recommended this book to several of my friends.

The Eternal Ones, by Kirsten Miller. Tennessee teenager Haven has always had visions of a past life, in which she was a girl named Constance whose doomed love for a boy named Ethan ended in disaster and death. But when she sees tabloid-TV coverage of an infamous celebrity named Iain Morrow, she is certain that she recognizes Ethan, and so when she turns 18 she heads up to New York City to find him. She finds that Iain feels their connection as well, and a love affair soon begins between the two...but soon Haven has doubts: Is Iain really Ethan, or could he be the person behind the deaths of Constance and Ethan in that past existence? Enlisting the help of a secret society with knowledge of reincarnation, Haven determines to find out the truth without reliving every detail of Constance's past.

Elizabeth's take: I loved this book! It was impossible to put down once I'd started. The author keeps you guessing constantly about the characters, their motives, and their intentions. The plot twists and bittersweet ending make it one of my favorite books.

Mockingbird, by Kathryn Erskine. This winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Young Readers is about Caitlin, a 10-year-old girl with Asperger's syndrome whose older brother has been killed in a school shooting. Told with remarkable sensitivity and insight from Caitlin's own perspective, it takes the reader through her attempt to deal with the tragedy herself, and to help her devastated father to weather the grief as well.

Elizabeth's take: This book was really touching, and offered an interesting point of view. It is refreshing to see things from the perspective of a person who doesn't view things the same way as most people.

[Cover images courtesy of Candlewick Press (Bloodline Rising) and Penguin USA (others).]

Bloodline Rising, by Katy Moran. Written more as a "companion" than a sequel to Moran's earlier British Dark Ages tale Bloodline, this novel tells the story of Cai, a clever young thief in seventh-century Constantinople. With his father away at war, he is betrayed by a rival and sold as a slave to a ship heading north, to Britain—which happens to be where his parents come from. He is taken in by a lord who clearly knew his parents and put to work as a spy amid major political intrigue...but soon finds that the man who took him in may have had something to do with his parents' departure from Britain.

Elizabeth's take: This book was suspenseful and had complex, believable characters. I couldn't put it down and could barely believe the twist in the ending! I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys stories full of danger, tension, and action.

Virals, by Kathy Reich. The first work for young readers by this forensic anthropologist, the novelist behind the TV series Bones, and the initial entry in a new sci-fi/suspense series, Virals is about 14-year-old Tory (she's the niece of Temperance Brennan, the character played by Emily Deschanel on the TV show), who must go live with the marine-biologist father she's never known on a small South Carolina island after her mother is killed in an accident. She soon finds a similarly scientific-minded group of kids to hang out with, and before long they've noticed something strange about the nearby Loggerhead Research Institute. But after they rescue a wolf-dog puppy from the laboratory, they're exposed to a canine virus that changes their DNA, heightening their senses and reflexes—which turns out to come in handy, since they end up with a cold-case murder on their hands.

Elizabeth's take: This sci-fi mystery was amazing! The action and creepy science projects kept me engrossed from beginning to end. I've already recommended this book to several of my friends.

The Eternal Ones, by Kirsten Miller. Tennessee teenager Haven has always had visions of a past life, in which she was a girl named Constance whose doomed love for a boy named Ethan ended in disaster and death. But when she sees tabloid-TV coverage of an infamous celebrity named Iain Morrow, she is certain that she recognizes Ethan, and so when she turns 18 she heads up to New York City to find him. She finds that Iain feels their connection as well, and a love affair soon begins between the two...but soon Haven has doubts: Is Iain really Ethan, or could he be the person behind the deaths of Constance and Ethan in that past existence? Enlisting the help of a secret society with knowledge of reincarnation, Haven determines to find out the truth without reliving every detail of Constance's past.

Elizabeth's take: I loved this book! It was impossible to put down once I'd started. The author keeps you guessing constantly about the characters, their motives, and their intentions. The plot twists and bittersweet ending make it one of my favorite books.

Mockingbird, by Kathryn Erskine. This winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Young Readers is about Caitlin, a 10-year-old girl with Asperger's syndrome whose older brother has been killed in a school shooting. Told with remarkable sensitivity and insight from Caitlin's own perspective, it takes the reader through her attempt to deal with the tragedy herself, and to help her devastated father to weather the grief as well.

Elizabeth's take: This book was really touching, and offered an interesting point of view. It is refreshing to see things from the perspective of a person who doesn't view things the same way as most people.

[Cover images courtesy of Candlewick Press (Bloodline Rising) and Penguin USA (others).]

October 28, 2011

New Books: The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth

I wrote last year (have I really been doing this that long already?) about my premature attempt to read The Phantom Tollbooth with my then-five-year-old, so it's safe to say that Norton Juster's classic is one of my own favorites. (It even made the cut on a list of personal picks I had to come up with for a publishing course when I was 21, alongside Homer, Hammett, and Ford Madox Ford. Looking back, I simultaneously smile at pretentious youth and realize with some surprise that I might still pick the same authors.)

with my then-five-year-old, so it's safe to say that Norton Juster's classic is one of my own favorites. (It even made the cut on a list of personal picks I had to come up with for a publishing course when I was 21, alongside Homer, Hammett, and Ford Madox Ford. Looking back, I simultaneously smile at pretentious youth and realize with some surprise that I might still pick the same authors.)

The brand-new Annotated Phantom Tollbooth is aimed directly at parents like me. It's exactly what it says it is: An extra-wide edition of the book, so designed to leave room for "annotations" in the margins (by historian and critic Leonard S. Marcus) about the ideas and inspirations behind Juster's characters and situations, as well as illustrator Jules Feiffer's eternally memorable rendering of them.

Marcus has combed interviews with and notes by both author and illustrator for these nuggets (which include the fact that Feiffer's illustration of the eccentric Whether Man, one of the first of the many unusual characters Milo meets on his journey, is pretty much a drawing of Juster himself). In an extended introduction, Marcus also relates the story of the book's origin as an especially close collaboration between two men sharing not merely a project, but a house in Brooklyn Heights. (Since Juster did the cooking for the housemates, Feiffer has joked that had he not agreed to illustrate The Phantom Tollbooth, he would literally not have been able to eat.)

Now, I don't think this is necessarily the best edition of the classic to use to introduce the book to one's own kids, full of distractions—and fairly serious-minded distractions at that—as it is. But it's almost a must-have for any adult (or teen, or maybe even tween) for whom this book holds a special place. And since it seems to have had that effect on many of us, chances aren't bad that our own kids will, in due time, come to enjoy leafing through the pages of this edition to find out where these two visionaries got their brilliant ideas.

Oh, and a year later, Dash asked to revisit The Phantom Tollbooth—and this time, everything clicked; he was drawn right in. Maybe a parent's (unpressured) dreams can come true after all, sometimes....

[Cover image courtesy of Knopf Books for Young Readers]

The brand-new Annotated Phantom Tollbooth is aimed directly at parents like me. It's exactly what it says it is: An extra-wide edition of the book, so designed to leave room for "annotations" in the margins (by historian and critic Leonard S. Marcus) about the ideas and inspirations behind Juster's characters and situations, as well as illustrator Jules Feiffer's eternally memorable rendering of them.

Marcus has combed interviews with and notes by both author and illustrator for these nuggets (which include the fact that Feiffer's illustration of the eccentric Whether Man, one of the first of the many unusual characters Milo meets on his journey, is pretty much a drawing of Juster himself). In an extended introduction, Marcus also relates the story of the book's origin as an especially close collaboration between two men sharing not merely a project, but a house in Brooklyn Heights. (Since Juster did the cooking for the housemates, Feiffer has joked that had he not agreed to illustrate The Phantom Tollbooth, he would literally not have been able to eat.)

Now, I don't think this is necessarily the best edition of the classic to use to introduce the book to one's own kids, full of distractions—and fairly serious-minded distractions at that—as it is. But it's almost a must-have for any adult (or teen, or maybe even tween) for whom this book holds a special place. And since it seems to have had that effect on many of us, chances aren't bad that our own kids will, in due time, come to enjoy leafing through the pages of this edition to find out where these two visionaries got their brilliant ideas.

Oh, and a year later, Dash asked to revisit The Phantom Tollbooth—and this time, everything clicked; he was drawn right in. Maybe a parent's (unpressured) dreams can come true after all, sometimes....

[Cover image courtesy of Knopf Books for Young Readers]

October 24, 2011

New DVDs: Teeny Tiny and the Witch Woman...and More Spooky Halloween Stories

I've written a few times before about the wonderful Scholastic Storybook Treasures series of DVDs, which created animated shorts out of kid-lit classics past and present. For Halloween, they've got a new one out: Teeny Tiny and the Witch Woman . . . and More Spooky Halloween Stories, aimed at kids ages 4 to 9. It packages together five shorts, including the old-school-scary title story (this video was originally made way back in 1980) by Barbara K. Walker, and narrated with panache by Marie Rosulková.

We're big fans of just about every video in this series, but since (as I think I've mentioned before) our older son is a mini Tim Burton, obsessed with all things spooky and creepy, this DVD happens to be one of his all-time favorites. If you have a little one with similar leanings, or just need a good Halloween-themed video for the kids this year, you can't go wrong with this one.

Update: New Kideo, the company that puts out these Scholastic DVDs, is having a giveaway of this very one (plus another one) on Facebook currently!

[Image courtesy of Scholastic Storybook Treasures]

We're big fans of just about every video in this series, but since (as I think I've mentioned before) our older son is a mini Tim Burton, obsessed with all things spooky and creepy, this DVD happens to be one of his all-time favorites. If you have a little one with similar leanings, or just need a good Halloween-themed video for the kids this year, you can't go wrong with this one.

Update: New Kideo, the company that puts out these Scholastic DVDs, is having a giveaway of this very one (plus another one) on Facebook currently!

[Image courtesy of Scholastic Storybook Treasures]

October 19, 2011

New Music: Things That Roar

As I've mentioned before, it's always especially thrilling to get a great new children's CD from an artist I don't already know. Don't get me wrong: Our family eagerly looks forward to every new release from our favorite established artists, of course. But there's something special about happening on a gem without those prior expectations.

So I'm happy to report that the debut CD from Papa Crow (the recording moniker of Michigan-based singer-songwriter Jeff Krebs) belongs right up there with the latest Dan Zanes release. Things That Roar is quality indie folk-rock for kids, largely acoustic guitar (with some mandolin, ukelele, and steel guitar thrown in) in the vein of Zanes as well as James Taylor, Nick Drake, and the softer sides of Neil Young and R.E.M. (There's even a nod to Leonard Cohen, appropriately enough in the childhood fear–themed "I'm Not Afraid Anymore.") The 14 well-crafted songs cover basic kid themes (animals, balloons, growing families) in remarkably unsappy, satisfying ways; Krebs has the knack of letting a simple theme express itself without excess embellishment.

Papa Crow also capitalizes on simplicity's advantages in the music itself: His proficient but unflashy playing, and his and Kerry Yost's warm vocals, have had a soothing effect on parents and kids alike in our home. (This is all the more impressive when you read in the liner notes how the album was recorded: "at home late at night downstairs while the wee ones slept"—astounding, given how good these tracks sound. Technology, you continue to amaze me.)

Things That Roar feels like the ideal album to listen to with a toddler or infant—though my six-year-old loves it, too!—on a sleepy, snowy winter afternoon. It's nothing fancy, just (quietly) one of the year's best kids' CDs. I'm really glad I've had the chance to hear it.

[Cover image courtesy of Papa Crow]

So I'm happy to report that the debut CD from Papa Crow (the recording moniker of Michigan-based singer-songwriter Jeff Krebs) belongs right up there with the latest Dan Zanes release. Things That Roar is quality indie folk-rock for kids, largely acoustic guitar (with some mandolin, ukelele, and steel guitar thrown in) in the vein of Zanes as well as James Taylor, Nick Drake, and the softer sides of Neil Young and R.E.M. (There's even a nod to Leonard Cohen, appropriately enough in the childhood fear–themed "I'm Not Afraid Anymore.") The 14 well-crafted songs cover basic kid themes (animals, balloons, growing families) in remarkably unsappy, satisfying ways; Krebs has the knack of letting a simple theme express itself without excess embellishment.

Papa Crow also capitalizes on simplicity's advantages in the music itself: His proficient but unflashy playing, and his and Kerry Yost's warm vocals, have had a soothing effect on parents and kids alike in our home. (This is all the more impressive when you read in the liner notes how the album was recorded: "at home late at night downstairs while the wee ones slept"—astounding, given how good these tracks sound. Technology, you continue to amaze me.)

Things That Roar feels like the ideal album to listen to with a toddler or infant—though my six-year-old loves it, too!—on a sleepy, snowy winter afternoon. It's nothing fancy, just (quietly) one of the year's best kids' CDs. I'm really glad I've had the chance to hear it.

[Cover image courtesy of Papa Crow]

Labels:

children's music,

kids' CDs,

kids' folk,

kids' music,

kids' rock,

new music,

Papa Crow

October 17, 2011

New Music: Songs from the Baobab

World music—a term no one really likes but no one has come up with a fully utilitarian replacement for, either—has always been a big part of children's music, going at least as far back as Pete Seeger's interpretations of folk songs from foreign lands. Today it's pretty much its own subgenre; Putumayo alone puts out several excellent world music (or world-music inspired) albums a year.

But I've never heard anything quite like the lovely Songs from the Baobab, a new book-CD combo from The Secret Mountain. It features 29 tracks of lullabyes and nursery rhymes in 11 different languages from Central and West Africa, sung by adults and children and played on indigenous instruments. The lullabyes, some essentially chants, are hypnotically soothing, perfect for lulling newborns and infants to sleep (as some have presumably done for generations). The more upbeat tracks, meanwhile, tend to be irresistible attention-grabbers, whose lyrics (translated for us in the accompanying book, which also features gorgeous illustrations by Elodie Nouhen, themed to the songs) are funny and moving and often profound.

Many parents will want to know more about these songs, and that informations is provided in the book—nation and language of origin, and in many cases interesting facts about the genesis of the songs themselves. Kids, meanwhile—and this is one of those albums that will appeal to a particularly broad age range of them, literally from newborns on up—will just love listening to them.

[Images courtesy of The Secret Mountain]

But I've never heard anything quite like the lovely Songs from the Baobab, a new book-CD combo from The Secret Mountain. It features 29 tracks of lullabyes and nursery rhymes in 11 different languages from Central and West Africa, sung by adults and children and played on indigenous instruments. The lullabyes, some essentially chants, are hypnotically soothing, perfect for lulling newborns and infants to sleep (as some have presumably done for generations). The more upbeat tracks, meanwhile, tend to be irresistible attention-grabbers, whose lyrics (translated for us in the accompanying book, which also features gorgeous illustrations by Elodie Nouhen, themed to the songs) are funny and moving and often profound.

Many parents will want to know more about these songs, and that informations is provided in the book—nation and language of origin, and in many cases interesting facts about the genesis of the songs themselves. Kids, meanwhile—and this is one of those albums that will appeal to a particularly broad age range of them, literally from newborns on up—will just love listening to them.

[Images courtesy of The Secret Mountain]

October 13, 2011

New(ish) Books: Hera: The Goddess and Her Glory

I wrote my very first post on this blog about the first two volumes in George O'Connor's Olympians series of graphic novels about the ancient Greek gods, so I'm a little ashmaed that it took me this long to get around to the third installment. (I mean, the fourth is just around the corner.) I spent much of that previous post marveling over O'Connor's ability to create compelling, action-packed, illustration-driven narratives while remaining remarkably true to both the letter and the tone of the ancient mythology. And if anything, he trumps himself in Hera: The Goddess and Her Glory.

As the author points out himself in the book's end notes, the queen of Olympus is a tricky subject, portrayed in most of the best-known myths as a shrewish wife and a vindictive punisher of both the various mortal women who are seduced by her husband, Zeus, and their progeny by him. Yet O'Connor has found a way to add a feminist slant to Hera's story—one that doesn't feel the least bit forced—by smartly mining some of the lesser-known variants on these stories, particularly the ones surrounding Herakles. (His very name—which translates as "the glory of Hera"—gives an author a lot to work with, and as his subtitle indicates, O'Connor doesn't disappoint.). This may be the former classics major in me speaking here, but I'm blown away by the extent of the author's research, and even more by what he's able to do with it.

Mind you, Hera is also every bit the engrossing page-turner that O'Connor's previous two Olympians books were; our six-year-old was difficult to separate from Zeus: King of the Gods and Athena: Grey-Eyed Goddess for the better part of a year, and this situation looks no different. (If anyone doubts my word, here's some direct-source backup for Hera's immense kid appeal.) All the Olympians books are in classic comic-book style (by which I mean the comic-book style of my childhood, naturally!), and it once again suits these tales perfectly. While I believe I have seen the labors-of-Herakles/Hercules stories executed in a comic-book format before somewhere or other before, the difference here is that O'Connor's is a really good graphic novel, one you—I mean, a kid—can read happily alongside the top entries in the genre. There's a reason these myths have had such staying power through the millennia—and O'Connor has captured it in these pages.

Can't wait for Hades....

P.S.: I just discovered that O'Connor also has a truly awesome Olympians website as well, with background on the mythology and the cast of characters, activities for kids, even resources for teachers! It will clearly be a challenge to keep Dash off the computer this month.

[Cover image courtesy of First Second Books.]

As the author points out himself in the book's end notes, the queen of Olympus is a tricky subject, portrayed in most of the best-known myths as a shrewish wife and a vindictive punisher of both the various mortal women who are seduced by her husband, Zeus, and their progeny by him. Yet O'Connor has found a way to add a feminist slant to Hera's story—one that doesn't feel the least bit forced—by smartly mining some of the lesser-known variants on these stories, particularly the ones surrounding Herakles. (His very name—which translates as "the glory of Hera"—gives an author a lot to work with, and as his subtitle indicates, O'Connor doesn't disappoint.). This may be the former classics major in me speaking here, but I'm blown away by the extent of the author's research, and even more by what he's able to do with it.

Mind you, Hera is also every bit the engrossing page-turner that O'Connor's previous two Olympians books were; our six-year-old was difficult to separate from Zeus: King of the Gods and Athena: Grey-Eyed Goddess for the better part of a year, and this situation looks no different. (If anyone doubts my word, here's some direct-source backup for Hera's immense kid appeal.) All the Olympians books are in classic comic-book style (by which I mean the comic-book style of my childhood, naturally!), and it once again suits these tales perfectly. While I believe I have seen the labors-of-Herakles/Hercules stories executed in a comic-book format before somewhere or other before, the difference here is that O'Connor's is a really good graphic novel, one you—I mean, a kid—can read happily alongside the top entries in the genre. There's a reason these myths have had such staying power through the millennia—and O'Connor has captured it in these pages.

Can't wait for Hades....

P.S.: I just discovered that O'Connor also has a truly awesome Olympians website as well, with background on the mythology and the cast of characters, activities for kids, even resources for teachers! It will clearly be a challenge to keep Dash off the computer this month.

[Cover image courtesy of First Second Books.]

October 6, 2011

New Music: Little Nut Tree

Back in the anxious days before the arrival of my first son, I remember a work colleague who was already a parent asking me if I had any Dan Zanes albums yet. I didn't know the name, and she looked at me a little incredulously across the divide that is parenting before smiling and saying, "You're probably going to playing him a lot. And you'll be happy about that."

She was right. Maybe I'm partially biased for having lived in his home turf of Brooklyn for two of those early parenting years, but I think of Zanes as the quintessential modern children's musician, the archetype who encapsulates everything that sets the genre apart today from years past. Indie cred from a band popular with the generation that's now knee-deep in parenting? Check. (Zanes was the frontman for the Del Fuegos.) Eclectic guitar-based musical style featuring a dizzying array of guest stars, some of the celebrity variety (Deborah Harry, Natalie Merchant), others simply great musicians? Check. Known for putting on irresistibly charming and audience-friendly stage shows, no matter how large his popularity and the associated venue size grows? Check.

Zanes was one of the first musicians to nail the sweet spot of music for kids that their parents also actually enjoyed listening to. By this time, it's easy to take him almost for granted among the panoply of artists creating kid tunes with adult-music sounds, from rock to punk to hip-hop. But all along, Zanes and his band of "Friends," as he labels his band and guest artists each time out, have been putting out CD after CD of great music, expertly mixing traditional songs from the U.S. and around the globe with inspired original compositions.

On his latest, Little Nut Tree, Zanes and company maintain his high standard, with seeming (though surely not actual) effortlessness. In his accustomed laid-back, breezy style, he and his guests—this time including the likes of Sharon Jones and Andrew Bird as well as old Friends Rankin Don/Father Goose and the wonderful Barbara Brousal—offer up sweet songs from Jamaica, Haiti, Tunisia, and the American Populist movement of the 1890s, as well as a number of Zanes's own original compositions. As always, the arrangements and the playing are top-notch, the mood is upbeat and celebratory, and the overall effect is one big smile.

For me, Little Nut Tree is almost musical comfort food—sort of a continuing representation of the core of my existence as a parent—and I see it has a similar effect on my kids, especially my older son, who's been listening to Zanes's music (thanks to that colleague) from the very beginning. And for parents as unfamiliar with the artist as I was way back when: You're probably going to be playing him a lot. Go ahead and start with this one. In the meantime, feel ancient with me via this old Del Fuegos track, featuring some shots of the artist before the bright-colored jackets:

[Cover image courtesy of Dan Zanes & Friends]

She was right. Maybe I'm partially biased for having lived in his home turf of Brooklyn for two of those early parenting years, but I think of Zanes as the quintessential modern children's musician, the archetype who encapsulates everything that sets the genre apart today from years past. Indie cred from a band popular with the generation that's now knee-deep in parenting? Check. (Zanes was the frontman for the Del Fuegos.) Eclectic guitar-based musical style featuring a dizzying array of guest stars, some of the celebrity variety (Deborah Harry, Natalie Merchant), others simply great musicians? Check. Known for putting on irresistibly charming and audience-friendly stage shows, no matter how large his popularity and the associated venue size grows? Check.

Zanes was one of the first musicians to nail the sweet spot of music for kids that their parents also actually enjoyed listening to. By this time, it's easy to take him almost for granted among the panoply of artists creating kid tunes with adult-music sounds, from rock to punk to hip-hop. But all along, Zanes and his band of "Friends," as he labels his band and guest artists each time out, have been putting out CD after CD of great music, expertly mixing traditional songs from the U.S. and around the globe with inspired original compositions.

On his latest, Little Nut Tree, Zanes and company maintain his high standard, with seeming (though surely not actual) effortlessness. In his accustomed laid-back, breezy style, he and his guests—this time including the likes of Sharon Jones and Andrew Bird as well as old Friends Rankin Don/Father Goose and the wonderful Barbara Brousal—offer up sweet songs from Jamaica, Haiti, Tunisia, and the American Populist movement of the 1890s, as well as a number of Zanes's own original compositions. As always, the arrangements and the playing are top-notch, the mood is upbeat and celebratory, and the overall effect is one big smile.

For me, Little Nut Tree is almost musical comfort food—sort of a continuing representation of the core of my existence as a parent—and I see it has a similar effect on my kids, especially my older son, who's been listening to Zanes's music (thanks to that colleague) from the very beginning. And for parents as unfamiliar with the artist as I was way back when: You're probably going to be playing him a lot. Go ahead and start with this one. In the meantime, feel ancient with me via this old Del Fuegos track, featuring some shots of the artist before the bright-colored jackets:

[Cover image courtesy of Dan Zanes & Friends]

October 5, 2011

New Books: Learning to Play the Piano for the Very Young

Shortly after we moved to the suburbs, we had the insane luck of acquiring a baby grand piano for just the cost of moving it about five blocks. (I remain in your eternal debt, Craigslist.) I don't play myself, but my wife does, and she remembers learning as one of her warmest childhood memories. To this day, even a few uninterrupted minutes at the piano is one of her favorite ways to relax and unwind.

This, as I know from friends' anecdotes about martinet teachers, is not everyone's experience of learning to play an instrument. So while we both would love our sons to make use of this gift from the suburban gods, we haven't pushed the issue; we decided to let the piano come to them, as it were. Both are showing interest in music in general, and the piano in particular, but the three-year-old doesn't have the attention span for any actual instruction yet, in our opinion. And to be honest, neither does the six-year-old, Dash, for whom the required focus remains something of a weak point.

So thus far, the piano has been more a lark for the kids than anything else. My wife has made some basic attempts at showing Dash how to read music, but not much more. We were still in this holding pattern when we came across the new book Learning to Play Piano for the Very Young, by Debbie Cavalier and Marty Gold. (I knew of Cavalier already from her Debbie and Friends children's-music albums, but she also happens to be dean of continuing education at Berklee College of Music; Gold, her grandfather, is a former orchestra leader who was also an A&R man for RCA in the 1950s and '60s.)

It's a 24-page primer aimed at preschoolers, but it works well even for an early grade-schooler without any training like Dash at getting the basic concepts across—the association of notes with letters, say. It's helpfully interactive--asking kids to write in finger numbers and note names—and just organized enough to help a child in a playful, not overly task-driven, manner. It slowly works up to getting kids to play simple, familiar songs ("Twinkle, Twinkle" and the like) with their right hand. At least for a book-obsessed kid like Dash, just seeing these basic concepts on paper was immensely helpful. At a time in his life when he wasn't ready for more formal methods of instruction, he dove into Cavalier and Gold's book and seemed to grasp its lessons—some of which my wife had been trying to get across for months—almost instantly.

Now, the jury is still out—still being selected, really—on whether Dash will take to the piano, or get beyond the initial stages at all. But in terms of teaching him the building blocks of piano in a low-key, undemanding way, and thus setting him up to take the next steps if he so desires down the road, Learning to Play Piano for the Very Young is just what we didn't even know we were looking for.

[Images courtesy of Debbie Cavalier Music]

September 30, 2011

New...Blogs!: Kid Pop and Beyond

When I started working at Cookie magazine and took over editing its children's-entertainment section, I didn't know that I was among the most fortunate magazine editors of all time. But I was, because Christopher Healy wrote the section, and his immense knowledge of children's literature, music, movies, and games, combined with his superb writing and insights, made my job incredibly, absurdly easy. Along the way, he also taught me just about everything I know about covering the subject; there is no question that if I'd never met Chris, You Know, for Kids would not exist.

So I'm thrilled to announce that Chris has launched his own blog, Kid Pop … and Beyond. He explains its mission fully over there, so I won't step on that too much, but in a nutshell he's aiming to cover a subject close to my heart, and I suspect those of most readers of this blog as well: kids' entertainment with crossover adult appeal. I encourage anyone who reads this blog to check it out—in fact, since I'll be frequenting his posts regularly as a reader myself, maybe I'll see you over there!

So I'm thrilled to announce that Chris has launched his own blog, Kid Pop … and Beyond. He explains its mission fully over there, so I won't step on that too much, but in a nutshell he's aiming to cover a subject close to my heart, and I suspect those of most readers of this blog as well: kids' entertainment with crossover adult appeal. I encourage anyone who reads this blog to check it out—in fact, since I'll be frequenting his posts regularly as a reader myself, maybe I'll see you over there!

Labels:

blogs,

Christopher Healy,

Cookie magazine,

new blogs

September 23, 2011

New Books: I Want My Hat Back

Every now and then, you run into a book that establishes its author—someone whose work you weren't familiar with—as a force to be reckoned with. It happens with books for adults, and it certainly happens with kid lit; we've all heard the stories of Maurice Sendak's meteoric entry into the pantheon with Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen, while Brian Selznick's about-to-be-a-Scorsese-film The Invention of Hugo Cabret is a more recent example.

Well, allow me to nominate Jon Klassen as another entry in the ledger. His first picture book, I Want My Hat Back, has such a strong, whimsical yet black-humor-laden voice to go with its striking, lovely illustrations that it immediately places Klassen among the leading lights of his field.

It's all the more remarkable for its plot's simplicity: An exceedingly deadpan bear has lost his hat, and goes from animal to animal asking if any of them has seen it. They are, in various ways, of little help—one has seen a hat but not the bear's hat; another has seen no hats at all—but one rabbit's manic response that he's seen nothing, nothing at all, strikes our protagonist in retrospect as suspicious. His reaction to this realization leads to the book's delightful, unexpectedly dark punch line, which will fill the wicked minds of kids and parents alike with glee. (Lemony Snicket is a fan, which may be all you need to know.) Klassen has created an instant classic, and I can't wait to see what he comes up with next.

[Photo: Whitney Webster.]

Well, allow me to nominate Jon Klassen as another entry in the ledger. His first picture book, I Want My Hat Back, has such a strong, whimsical yet black-humor-laden voice to go with its striking, lovely illustrations that it immediately places Klassen among the leading lights of his field.

It's all the more remarkable for its plot's simplicity: An exceedingly deadpan bear has lost his hat, and goes from animal to animal asking if any of them has seen it. They are, in various ways, of little help—one has seen a hat but not the bear's hat; another has seen no hats at all—but one rabbit's manic response that he's seen nothing, nothing at all, strikes our protagonist in retrospect as suspicious. His reaction to this realization leads to the book's delightful, unexpectedly dark punch line, which will fill the wicked minds of kids and parents alike with glee. (Lemony Snicket is a fan, which may be all you need to know.) Klassen has created an instant classic, and I can't wait to see what he comes up with next.

[Photo: Whitney Webster.]

September 21, 2011

New Games: Quallop

My children are only six and three, and my wife is not much of a game-player. So until recently, when it came to research on board games of any kind, I was kinda on my own. (Video games, of course, are another story—even the three-year-old loves them already. Scary. But I digress...)

Happily for my continuing attempts to relive my own board game–laden childhood, though, Dash has now reached an age and attention span that allows for options more advanced than Hi Ho Cherry-O. We just introduced him to Clue, for instance, and that was a great success, once I got over my horror that they've changed the rules a bit in the 25-plus years since I played it last. (I'm still trying to find my old version in the attic.)

What's really fun to find, though, is a new game that's simple enough for kids this age, but also smart enough to engage not only kids' minds, but those of the adults who'll inevitably be playing with them. Even better, at least for my family's current needs, is one that's made for just two players, not four-but-you-can-sort-of-play-lamely-with-fewer—and such games are very hard to find.

Quallop, which melds dominoes with a 2-D version of Connect Four

As if that weren't enough, the design and packaging are excellent as well—this is a Chronicle Books product, after all: The board folds into a nifty little colorful case that encompasses all the cards and the rule sheet, then holds itself closed thanks to a hidden magnet. Obviously, this makes Quallop a pretty fabulous travel game; I think it's going to be come a stand-by on our trips this fall and winter.

[Photos: Whitney Webster]

Labels:

board games,

Chronicle Books,

Clue,

Connect Four,

dominoes,

new games,

Quallop

September 16, 2011

New Books: The Iron Giant